Even with the best of intentions, unexamined school assignments, class activities, books, and materials can distort history, perpetuate myths and stereotypes, and marginalize the experiences of students who are not White or Christian or otherwise conforming to supposed norms.

For example, children’s books about Columbus in many school and classroom libraries portray Columbus as a benign, brave explorer, while depicting the indigenous Taino people as willing, even happy, guests on the journey back to Spain, effectively erasing their brutal treatment and enslavement.

Another example involves asking children to create the flags of their ancestor’s countries; those descended from slaves or whose family histories were lost in tragic events like the Holocaust at best cannot participate in the activity without fabricating a response and at worst experience the marginalization and sense of otherness that comes from ignoring their families’ experiences of slavery or genocide.

Even reenactments intended to teach kids about difficult moments in history can misfire. For example, children in one classroom were asked to stand crowded within squares taped on the floor to “simulate” the conditions on slave ships. By equating the horrific experiences of the slaves on those ships with standing close to a friend in a classroom, the exercise unintentionally trivialized the painful struggles of these enslaved people (for more information about the problems with classroom reenactments and learning history, see Jones, 2020).

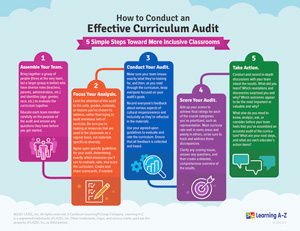

So how should teachers strive to create a more inclusive curriculum? The following sets of questions reflect principles that can be applied to audit curriculum for inclusive teaching practices, cultural awareness and responsiveness, and the use of diverse teaching materials:

- Recognize students' rights to make choices about their reading and writing and encourage them to read and listen to books representing who they are (Souto-Manning, 2020). Do books and writing opportunities reflect the interests of students in the classroom? Do students choose what they read and write, at least some of the time? Do characters in the books look like the students in your classroom? Are people who have historically been marginalized included as characters in stories of contemporary everyday life, in addition to historical fiction or biography?

- Provide multiple and balanced points of view. When teaching social studies, history, or current events, are multiple perspectives included? If a book presents a single perspective, can other books be added to provide another point of view? Rather than teaching historical events solely from the perspective of White Americans or Europeans, can books and learning activities widen the lens to also examine the lives and experiences of indigenous people in these time periods and how events affected them? When reading books that present only one perspective, distort facts, or mythologize history, can students be engaged in discussions about how power and privilege can reshape stories? Can students’ emotional connections to holidays or celebrations be acknowledged and honored without reinforcing problematic mythologies?

- Honor different forms of expression, such as oral storytelling, song, visual art, and video (Souto-Manning, 2020). What forms of expression and communication do students engage in outside of school? Can those forms of expression be incorporated into the classroom, as bridges to academic learning? For example, do families tell stories about their children or family history? If so, can students record, transcribe, or retell family stories?

- Avoid perpetuating stereotypes and marginalizing students’ experiences. Do books contain stereotypes in illustrations or text? If they do contain stereotypes, can students be engaged in discussions about who is telling the story, why characters, communities, or cultures might be portrayed in stereotypical ways, and the harm stereotypes cause? Are assumptions being made about what is the “norm” for students’ family backgrounds or experiences? If learning activities center some students’ experiences and marginalize other students, can they be reframed, revised, or reimagined to be more inclusive? Do books and curriculum materials provide students with accurate, authentic glimpses into the experiences of others unlike themselves?

- Respond to students’ learning needs: Does the curriculum contribute to “one-size-fits-all” teaching that doesn’t take students’ unique individual interests and specific learning needs into account? Do books, materials, and instructional approaches actively engage all students in learning?

While this list of principles and questions is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to curriculum review, they can provide a starting point for examining teaching and learning practices for inclusivity and cultural responsiveness.

Complimentary Offer: Help All Students Feel Seen, Heard, and Understood

Comprehensive SEL Meaningful Conversations resources in Raz-Plus are designed to foster self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making:

- Deliver highly engaging, multi-format materials for students

- Access full instructional support

- Guide age-appropriate, inclusive, and respectful discussions

- Help students develop SEL competencies

Try them with your students for free!

GET FREE ACCESSReferences

Jones, S. (2020). Ending curriculum violence.

Learning for Justice, 64

Souto-Manning, M. (2020).

In the pursuit of justice: Students’ rights to read and write in elementary school. Champaign, Illinois: National Council of Teachers of English.